The coming New Year heralded new administrative regulations for marijuana in the State of Oregon. These changes came through the Oregon Liquor and Cannabis Commission (OLCC) rulemaking process. That process, in turn, stems from cannabis laws passed by the Oregon legislature earlier this year.

Common Ownership Issues

Common Ownership Definition

Oregon allows verticality in its regulated cannabis program. Some of the new rules resulted from the reality that licenses are often commonly owned as between producers, retailers, and so forth. The Oregon legislature addressed this in SB 408, which provides:

As used in this section, “commonly owned” means, as further defined by the Oregon Liquor Control Commission by rule, that a person included on an application for a license under ORS 475B.070 has an interest in or authority over the management of another entity for which a license has been issued under ORS 475B.070.

This statutory change resulted in the OLCC revising the definition of common ownership in OAR 845-025-1015. to the following:

(21) “Common Ownership” (a) Means any commonality between individuals or legal entities named as applicants or persons with a financial interest in a license or business proposed to be licensed that have a financial interest or management responsibilities for an additional license or licenses.

(new language in italics). The business reality of common ownership between licenses of the same and different types led the OLCC to revise several other rules, discussed below.

Transfer Privileges

Among the significant changes were those to transfer privileges between the four different types of licenses: producer, processor, wholesaler, and retailer.

For years the rules have restricted to whom marijuana growers may sell, transfer, transport and deliver their product. Among the significant restrictions were prohibitions on producer-to-producer transfers. Those restrictions have been lifted, in large part:

- Marijuana growers may now engage in producer-to-producer sales, transfers, transports and deliveries of usable marijuana where the producers are under common ownership.

- Marijuana producers may also transfer whole, non-living marijuana plants removed from a growing medium to the licensed premises of another producer under common ownership. Previously such transfers were only permitted to processors, wholesalers, nonprofit dispensaries and research certificate holders.

- Marijuana producers may also move transfer kief between producers with common ownership.

In addition, a marijuana producer may now purchase and receive:

- marijuana and marijuana plants from a producer under common ownership;

- marijuana produced by the licensee that was not processed by a processor;

- cannabinoid products, cannabinoid extracts and cannabinoid concentrates from a marijuana processor that were made using only marijuana produced by the receiving producer;

- up to 200 marijuana seeds in total per month from any sources within the State of Oregon other than a licensee, laboratory licensee, or research certificate holder; and

- marijuana seeds from a retailer.

The OLCC also simplified the language retailer-to-retailer purchases by simply permitting a retailer to purchase, possess, or receive “marijuana items from a retailer under common ownership.” Previously, the rule described the class of persons eligible for such transactions as being those owned by “the same or substantially the same persons.”

How (and whom) the new rules help

The principal benefits of these change will be for business structures have a horizontal component at the marijuana growing level, as well as those that have a vertical organizational structure.

The changes to producer transfers in particular should reduce internal transaction costs, since many operations were forced to obtain a wholesale license to engage in producer-to-producer transactions with the wholesale license acting as the “man-in-the-middle” for these kind of deals.

Another benefit may accrue to multi-license operations that are engaged in the sale of one entity and who desire to transfer inventory between other commonly held assets.

Regulation of Hemp

Oregon’s New Hemp Rules

Under the new rules, “Adult Use Cannabis Item” means, in part, “[a]n industrial hemp commodity or product that:

- Contains 0.5 milligrams or more of any combination of: (a) total delta-9-THC; (b) any other THCs or tetrahydrocannabinolic acid, including delta-8-tetrahydrocannabinol; or (c) any other cannabinoids advertised by the manufacturer or seller as having an intoxicating effects;

- Contains any quantity of artificially derived cannabinoids (i.e., “a chemical substance that is created by a chemical reaction that changes the molecular structure of any chemical substance derived from the plant Cannabis family Cannabaceae”); or

- The testing done in accordance with ORS 571.330 or 571.339. was performed using a method with a LOQ that is not sufficient to demonstrate that the total delta-9-THC does not exceed 0.5 milligrams.

OAR 845-026-0300.

The rules further provide that if the hemp commodity or product qualifies as an adult use cannabis item, it cannot be sold or delivered to a person under 21 years of age. However, an exception exists for any hemp item sold by an OLCC-licensed marijuana retailer that:

- is registered to sell or deliver marijuana items to a registry identification cardholder who is 18 years of age or older; or

- is registered under the state’s medical marijuana program.

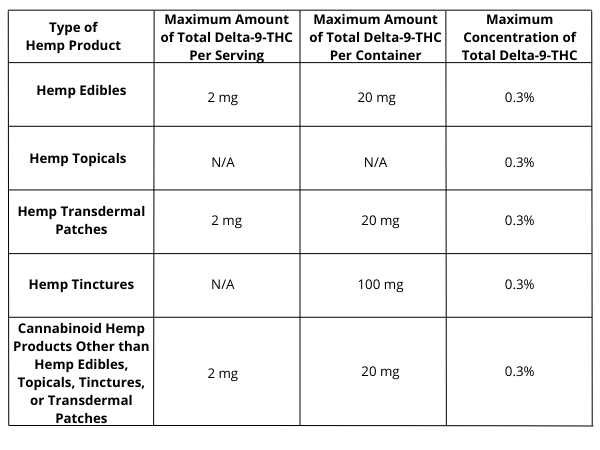

In addition to limiting the sale and distribution of these products to adults, the OLCC rules also restrict these activities outside the recreational market to adult use cannabis products that do not exceed specific maximum amounts of THC by more than ten percent (10%). These limits differ based on the product category, summarized as follows:

See OAR 845-026-0400 for full table.

Note that these limits become operative on July 1, 2022. In addition, these limits do not apply to hemp products containing less than 0.3% total THC sold and distributed outside of Oregon.

How the New Hemp Rules Were Made

These newly adopted limits reflect some of the recommendations received by the OLCC during the notice-and-comment period. One of these changes pertains to the much-needed distinction between single v. multi serving products. In the July 2021 version, OLCC rules imposed a 0.5 mg per package limit for total THC. This limit subjected 30- and 60-day serving products, such as dietary supplements, to the same limits as single serving products like edibles. This, in turn, was potentially more burdensome to certain industries, such as companies marketing dietary supplements.

What happens next

Despite these changes, many stakeholders remain concerned with the negative consequences these rules may create for the hemp industry. For instance, restricting access to these products and putting an age limit on all adult use cannabis products potentially misclassifies safe, non-intoxicating hemp products. Such misclassification sends a false message that all these products pose a public health or safety risk. Moreover, retailers which now have to check IDs before selling these products may be deterred from carrying these products altogether. This, in turn, could stifle economic opportunities for the entire industry and reduce consumer choices.

Obviously, the OLCC sees these changes as positive. Steve Marks, the OLCC Executive Director, called the rules “some of the best, most well-explained standard-setting that’s been put out surrounding these products” in a U.S. market rife with uncertainty and confusion.

Changes Affecting Artificially Derived Cannabinoids

In the big picture, Oregon stakeholders knew new regulations would be adopted in December 2021, but most hoped for less stringent final rules. Unfortunately for the industry, the OLCC decided to proceed with the adoption of rather stringent regulations, including burdensome rules impacting the manufacture and sale of finished hemp products sold in the State.

Two of the most noteworthy changes impacting these products include:

- the prohibition on the sale and distribution of “adult use cannabis items” to minors as well as restrictions on the ability to sell these products outside the recreational market, which I covered last week; and

- burdensome requirements imposed on “artificially derived cannabinoids,” including the popular and lucrative cannabinoid: cannabinol (CBN), which is the topic of today’s post.

Reason for artificially derived cannabinoid rules

Back in March 2021, the OLCC released a public statement in which the agency expressed growing concern about the general availability–including to children–of unregulated, intoxicating products derived from hemp. Delta-8 THC was a primary example. To address this public health threat, the OLCC initiated the rulemaking process for Delta-8 THC and other psychoactive components of hemp that then fell outside the OLCC market. It also adopted emergency rules in July, which banned the sale of these “artificially derived cannabinoids” to minors under the age of 21.

Yet, in the month following the enactment of this emergency rules, the OLCC expanded the definition of the term “artificially derived cannabinoids” to include “semi-synthetic cannabinoids created from chemical reactions with cannabis-extracted substances,” including non-psychoactive cannabinoids like CBN.

Authorized artificially derived cannabinoid-related activities

The new OLCC rules distinguish between intoxicating and non-intoxicating artificially derived cannabinoids by imposing different sale restrictions on these products. Specifically:

- Beginning July 1, 2022, the sale of artificially derived cannabinoids won’t be allowed if sold outside of the OLCC recreational market; and

- Following the July 1 deadline, the sale of intoxicating artificially derived cannabinoids, such as Delta-8-THC, will be strictly prohibited inside and outside the OLCC market.

It is worth pointing out that the cutoff for the sale of CBN product is extended to July 1, 2023. Until then, OLCC licensees can continue to transfer, sell, transport, purchase, accept, return, or receive CBN and products containing artificially derived CBN as long as:

- The CBN product was manufactured in a facility with an Oregon Department of Agriculture (ODA) food safety license by an OLCC processor or ODA hemp handler;

- The CBN product is not intended for human inhalation;

- The CBN product is going to be sold at an OLCC-licensed retailer; and

- The CBN product meets the labeling requirements in OAR 845-025-7145.

After the July 1, 2023 deadline, OLCC licensees will be able to transfer, sell, transport, purchase, accept, return, or receive artificially derived cannabinoids and products containing artificially derived cannabinoids, including CBN products, provided the following conditions are met:

- The artificially derived cannabinoid is not impairing or intoxicating;

- The artificially derived cannabinoid or product is not intended for human inhalation;

- The artificially derived cannabinoid was manufactured in a facility with an ODA food safety license by an OLCC processor or ODA hemp handler;

- The artificially derived product meets the labeling requirements in OAR 845-025-7145;

- The artificially derived cannabinoid has been reported as a naturally occurring component of the plant Cannabis family Cannabaceae in at least three peer-reviewed publications; and

- The manufacturer of the artificially derived cannabinoid provides OLCC with a “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS) determination for the artificial cannabinoid.

Why the new rules hurt

Most of all, requirement #6 above is incredibly burdensome. This is because: (1) the FDA has yet to establish a federal regulatory framework for hemp-derived products (also, the agency has yet to approve any premarket approval submitted by hemp companies), and (2) this pre-approval process is long and onerous.

Many in the Oregon hemp industry see the OLCC’s decision to impose a GRAS determination requirement on artificially derived cannabinoids as arbitrary and unfair. Indeed, the OLCC does not impose such GRAS determination on naturally derived cannabinoids sold in the state. But regardless of where hemp companies making and selling artificially derived cannabinoid products stand on this issue, all will be required to make the necessary changes to comply with the new OLCC rules.

History of a Lack of Institutional Control

New rule: violation for a history of lack of institutional control

The OLCC places violations of rules in four categories with each having a different presumptive sanction/penalty. See Oregon Cannabis: What to Do If You Receive an OLCC Notice of Proposed License Cancellation or Other “Charging Document”. A Category I rule violation is the most serious as the presumptive penalty is license cancellation.

Among the many rule changes is the inclusion of a new type of Category I violation for “History of Lack of Institutional Control.” The new rule will be codified at OAR 845-025-8550, the full text of which is available here.

This new rule gives the OLCC authority to cancel, suspend, restrict or require mandatory training for any license and to impose a civil penalty if the OLCC “finds” or “has reasonable grounds to believe” there is a “history of lack of institutional control” involving the licensee’s operation of its business. Let’s unpack these terms.

The “reasonable grounds to believe” standard is bad for licensees

One unfortunate aspect or the rule is the “reasonable grounds to believe” language, as opposed to “finds.” The term “finds” has a fairly established meaning in the law and corresponds easily to settled evidentiary standards. In civil cases, for example, that standard is a preponderance of the evidence. In plainer English, preponderance just means more likely than not. For example: for a jury to find a breach of contract, the jury must find it more likely than not that a contract exists, was breached, and the breach caused damages.

The “reasonable grounds to believe” language is what many lawyers would call “squishy.” That is because what that language means in terms of the OLCC having to prove its case is less than clear. In the administrative law context, which is where licensees accused of violating a rule must defend OLCC accusations, this kind of language strongly favors the OLCC and represents a broad claim of enforcement power.

The OLCC is saying to licensees, in effect: “look, we don’t actually have to find (prove) you have a history of lack of institutional control, we just have to have a ‘reasonable ground to believe’ there is such a history.” As an attorney who regularly represents license holders in administrative proceedings, I am not fond of this kind of standard. It makes it too easy on the OLCC to impose its will on licensees. Indeed, the OLCC does not define anywhere exactly what it means to “reasonably believe” there is a violation … as opposed to actually finding a violation of the rule.

History of a lack of institutional control

Obviously, a critical component of the new rule is the definition of a “history of a lack of institutional control. Unlike the “reasonable grounds to believe” language, here at least the OLCC provided a detailed definition:

(2) A history of lack of institutional control:

(a) Means violations of Commission statutes or rules have been observed at the premises and the licensee failed to show adequate compliance measures, education of employees, agents, or licensee representatives on those compliance measures, and prompt action upon learning of deficiencies in compliance measures; and

(b) Is based on the nature, number and circumstances of the incidents, and can include incidents at the licensed premises that were not themselves the subject of violation charges.

(3) Behavior that is grounds for a sanction includes but is not limited to noncompliance with requirements relating to license privileges, security, tracking, testing, transportation, packaging and labeling, as well as prohibited and dishonest conduct.

Frequent / repeat rule violators beware

This new rule violation may be thought of as the OLCC seeking to clamp down on repeat offenders in cases where the past violations themselves have not led to the cancellation. In other words, licensees have compliance problems over and over, but no set of those violations was serious enough to warrant cancellation.

One positive aspect of the new rule is that the OLCC may require a compliance plan in lieu of issuing a notice to cancel or suspend a license. This coincides with recent changes toward a “fix it or ticket” approach to enforcement. Another positive aspect is that the rule expressly states a licensee may mitigate the history by showing the problems are not serious or persistent, and by demonstrating a willingness to fix the problems. So licensees should have at least one opportunity to fix problems before the OLCC seeks cancellation for a history of a lack of institutional control.

It will be interesting to see how and when the OLCC decides to flex this new authority. Perhaps it means the OLCC will take a closer look at marijuana businesses that some view as able to avoid meaningful sanction because they are essential “too big to fail.”

License Cancellation Criteria

The new rule applies to marijuana license cancellations under ORS 475B.256(1)(a)

So what conduct falls under this statute?

The text of the statute includes a wide swath to conduct. It provides that OLCC may revoke, suspend, or restrict a license, or require a licensee to or licensee representative to undergo training if the OLCC finds or has reasonable grounds to believe that the licensee or licensee representative:

(A) Has violated a provision of ORS 475B.010 (Short title) to 475B.545 (Severability of ORS 475B.010 to 475B.545) or a rule adopted under ORS 475B.010 (Short title) to 475B.545 (Severability of ORS 475B.010 to 475B.545).

(B) Has made any false representation or statement to the commission in order to induce or prevent action by the commission.

(C) Is insolvent or incompetent or physically unable to carry on the management of the establishment of the licensee.

(D) Is in the habit of using alcoholic liquor, habit-forming drugs, marijuana or controlled substances to excess.

(E) Has misrepresented to a customer or the public any marijuana items sold by the licensee or licensee representative.

(F) Since the issuance of the license, has been convicted of a felony, of violating any of the marijuana laws of this state, general or local, or of any misdemeanor or violation of any municipal ordinance committed on the premises for which the license has been issued.

ORS 475B.256. As should be apparent from this language, the statute gives the OLCC wide latitude in the exercise of its enforcement powers. However, the new rule cabins this power in some respects.

The new rule allows the OLCC to cancel a marijuana license only when the conduct poses a significant risk to public health and safety

The new rule is found in OAR 845-025-8590(2). It states that the Commission may cancel a license under the statute cited above “only when the conduct poses a significant risk to public health and safety.”

Conduct that constitutes a “significant risk” to public health and safety includes:

(a) Exercising licensed privileges while the license is suspended, or in violation of restrictions imposed on the license;

(b) Allowing minors at a processor license;

(c) Prohibited conduct involving a deadly or dangerous weapon or conduct that results in death or serious injury;

(d) Prohibited use of pesticides, fertilizers and agricultural chemicals;

(e) Diversion of marijuana, inversion of marijuana, or other conduct described in ORS 475B.186;

(f) Transferring or providing adulterated marijuana or hemp items to a licensee or consumer;

(g) Prohibited conduct by laboratory licensees as described in OAR 845-025-5075;

(h) Failure to meet testing requirements as described in OAR 845-025-5700, 333-007-300 to 333-007-0500 and 333, division 64;

(i) Intentionally destroying, damaging, altering, removing or concealing potential evidence, or attempting to do so, or asking or encouraging another person to do so.

Importantly, this list is not exclusive. So there may be other kinds of conduct that also poses a significant risk to health and safety.

The new rule is a good change for OLCC licensees

This language ought to be seen favorably for licensees facing cancellation. That is because the new language means that a mere violation of the ORS 475B.256(1)(a) is not enough. The OLCC must also establish that the conduct poses a significant risk to public health and safety. This changes part of the OLCC’s attempt to shift from enforcing the rules strictly (some may say punitive) manner, to more of a partnership approach with licensees. (See Oregon Marijuana: OLCC to Adopt “Fix-it or Ticket” Approach for Some Rule Violations). Let’s hope the OLCC sees it that way too as we move into 2022.